Some translations use the heading “The Parable of the Dishonest Manager” while others have it as “The Parable of the Shrewd Manager.” Whatever you call it, Jesus had a specific purpose in his presentation of this parable.

Jesus told his disciples an odd parable in which he used a dishonest manager as an example of shrewdness to teach a biblical principle of stewardship in ways that made it easier to understand.

Follow this summary on the Parable of the Shrewd or Dishonest Manager with this verse-by-verse commentary.

† Find Warren’s short summary at the bottom of page.

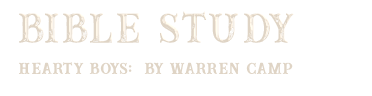

Click the list or the “bird” to enlarge and use Warren’s list of forty-four of Jesus’ parables (a PDF file with links to Scriptures).

Start Reading Warren’s Commentary . . .

Find his summary at the bottom.

par•a•ble [noun] a simple story used to illustrate the meaning of or a moral or spiritual lesson, as told by Jesus in the gospels

synonyms: allegory, moral story/tale, fable

Jesus’ Parable of the Shrewd Manager

Luke 16:1–15

Found only in Luke’s gospel, the Parable of the Shrewd Manager is sometimes called the Parable of the Unjust Steward or Unrighteous or Dishonest Steward. It’s important to understand that this parable, although spoken directly to his disciples, was also meant to be heard and appreciated by the Pharisees, so that they’d grasp its meaning. Speaking so that they heard his teaching, Jesus was pointing out to them that they, too, were sinners and, as a result, needed to feel regret and repent of their behavior because they, while considering themselves as being spiritually elite, had become lovers of money.

Jesus included this parable in a series of accounts that he made in response to the Pharisees, scribes, and teachers of the Law who’d complained that he’d intentionally sat down and eaten with tax collectors and other sinful types. Initially explaining why he’d associated with the likes of “sinners,” he spoke to them these three parables found in Luke 15: the Parable of the Lost Sheep, the Lost Coin, and the Prodigal Son. He followed by having his listeners focus on this Parable of the Shrewd Manager.

The Parable of the Shrewd Manager

A Parable of Wisdom and Folly, Regarding Stewardship

A 4-minute depiction of the Lord Jesus’ Parable of the Shrewd Manager (by 365 Bible)

• shrewd [adjective] having or showing sharp powers of judgment; astute; intelligent

Jesus told his disciples this story that sounds quite contemporary. A dishonest manager was about to lose his job because he’d misspent his employer’s assets. To avoid having to do manual labor or receive charity, he approached those who owed his employer money, then reduced their debts by forgiving a meaningful portion of each debtor’s amount owed to his master. He did this so that they’d be hospitable to him after he'd lost his job with the master. To our surprise, the employer commended the dishonest, albeit “shrewd” manager for his wise handling of his pending termination. However, it's important to note that the manager didn't praise the manager for his dishonesty, only for his cleverness. But why was he commended?

To answer that question, we need to realize that this parable acts as a bridge to connect the stories of the Prodigal Son (15:11–32) and the Rich Man and Lazarus (16:19– 31). Like the prodigal in the preceding story, our dishonest manager had “squandered” what was entrusted to him (15:13; 16:1). And, like the story that follows, today's parable begins with the phrase, “There was a rich man” (16:1, 19). Although our shrewd, dishonest manager didn’t repent (as the prodigal had done) or act virtuously (as Lazarus had), nonetheless he did something with the rich man’s wealth that reversed the existing order of things.

The text of this parable can be broken into three segments: the account itself in vv. 1–8; its application in vv. 9–13; and the parable’s warning in vv. 14–15. In v. 8, the Lord himself gives the key to his parable, which is that “the children of light,” in the conduct of their affairs, should emulate the wisdom and prudence of “the children of the world” in the conduct of their affairs. Let’s dig into the text and meaning of this “wisdom and folly” parable.

The Parable of the Shrewd Manager

16 1Jesus told his disciples: “There was a rich man whose manager was accused of wasting his possessions. 2So he called him in and asked him, ‘What is this I hear about you? Give an account of your management, because you cannot be manager any longer.

3“The manager said to himself, ‘What shall I do now? My master is taking away my job. I’m not strong enough to dig, and I’m ashamed to beg — 4I know what I’ll do so that, when I lose my job here, people will welcome me into their houses’ (Luke 16:1–4).

The opening clearly identifies Jesus’ disciples as the people to whom he told this parable. However, we’ll see in v. 14 that it’s possible that there was a mixed audience for his recitation, made up of disciples and Pharisees. In addition, the word “also” is included in v. 1a in a number of versions (ESV, RSV, NKJV, NCV, NASB, and KJV), suggesting that this parable is connected to the previous three in Luke 15 (mentioned atop this page in my opening paragraph) and that the audience was a mixed crowd of disciples and Pharisees. The parable was presented to benefit the disciples, but there is, therein, also a not-so-subtle critique of the Pharisees (vv. 14–15).

The parable begins with a rich man who meets with his steward/manager, informing him that he’ll be fired for mismanaging the rich man’s resources. The steward had authority over all of the master’s resources; he was permitted to transact business on his behalf, which would have required the steward to have an extremely high trust level. Although not readily evident at this point in the parable, the master probably wasn’t aware of the steward’s dishonesty. Ordinarily, stewards were slaves; but this one was evidently a free man, for he was neither punished nor sold but discharged. He was being released for alleged mismanagement, not fraud, which explains why he was able to conduct additional transactions before his release and why he wasn’t immediately tossed out on the street.

The sly steward, realizing that he’d soon be unemployed, made a few sharp-witted deals behind his master’s back by reducing the amounts owed by several of the master’s debtors. He granted the debtors attractive financial relief in exchange for his upcoming need for shelter when he’d eventually be relieved of his duties. When the master became aware of what the servant had done behind his back, instead of rebuking him he commended him for his “street smarts.”

5“So he called in each one of his master’s debtors. He asked the first, ‘How much do you owe my master?’

6“‘Nine hundred gallons of olive oil,’ he replied.

“The manager told him, ‘Take your bill, sit down quickly, and make it four hundred and fifty.’

7“Then he asked the second, ‘And how much do you owe?’

“‘A thousand bushels [about 30 tons] of wheat,’ he replied.

“He told him, ‘Take your bill and make it eight hundred’ (vv. 5–7).

For the first debtor whom the steward encountered (v. 5), the discounted amount owed to the master became 450 gallons of olive oil, which was quite valuable. Such a reduction of debt would have put the debtor under great obligation to the shrewd steward. For the second debtor, the 1,000 bushels of wheat that was owed to the master was reduced to 800 bushels. Note that the debtor himself altered the writing on the bill, to eliminate any uncertainty about it and prevent the steward’s handwriting to have been recognized — a shrewd move!

In vv. 8–13, Jesus emphasizes the point of his parable of the shrewd manager (unjust steward). Look closely at each verse, starting with vv. 8–9.

8“The master commended the dishonest manager because he had acted shrewdly. For the people of this world are more shrewd in dealing with their own kind than are the people of the light. 9I tell you, use worldly wealth to gain friends for yourselves, so that when it is gone, you will be welcomed into eternal dwellings” (vv. 8–9).

The Greek word phronimos for “shrewd,” in v. 8, can be translated as “prudent” or “wise.” The master liked what he saw in the steward’s resourcefulness; he commended him for being so shrewd and wise, but there’s nothing in the two verses that indicates that, after he was fired, he was dishonest in his dealings with the master’s debtors. In fact, he was able to get them to pay at least part or most of their bills, as opposed to the master receiving no payment at all from them.

Then the master told the steward to “use worldly wealth to gain friends for yourselves, so that when it is gone, you will be welcomed into eternal dwellings.” What does this mean? There’s nothing inherently righteous about money. In fact, the love of it is amoral! But Jesus may be telling us in this parable to use our money to advance the purposes of God’s kingdom, while we still have money or while we’re still alive. That is, when we support ministries that preach the gospel and bring it into other parts of the world, we’ll essentially receive people into our eternal dwellings as a result of our working in response to our being called to serve in the Great Commission (Matthew 28:16–20; Acts 1:8).

Jesus said in v. 8, “For the people of this world are more shrewd in dealing with their own kind than are the people of the light.” He was drawing a contrast between the “people of the world” (i.e., unbelievers) and the “people of light” (believers). People of light are equally shrewd and wise in the management of their affairs, using only those means and methods that are biblically permissible.

Unbelievers are wiser in things of this world than believers are about things of the world to come. The unjust steward demonstrated worldly wisdom through dishonest cunning and rascality by cheating his master. He made friends of his master’s debtors who’d then become obligated to care for him once he lost his job. Jesus referred to the Pharisees who’d been very clever in obtaining money, but unwise in how they dealt with spiritual and eternal matters. The master continued in v. 9 by telling the manager, “Use worldly wealth to gain friends for yourselves, so that when it is gone, you will be welcomed into eternal dwellings.”

That’s to say, the steward, a worldly-minded rascal, knew better how to deal with the worldly-minded master who was above him and the dishonest tenants beneath him, than a person of light knows how to deal with God who’s over him and his needy brethren who are around him. In v. 9, Lord Jesus was encouraging his followers to be generous with their wealth in this life so that, in the life to come, their new friends would receive them “into eternal dwellings.” He taught a similar principle about wealth in his Sermon on the Mount when he encouraged his followers to lay up treasures in heaven (Matthew 6:19–21).

Faithful or Dishonest Stewardship In verses 10–13, Jesus expands on the principle he highlighted in v. 9: If we can’t be faithful with earthly wealth, which isn’t even ours to begin with, how can we be entrusted with “true riches”? The “true riches” in v. 11 refers to stewardship and responsibility in God’s kingdom, along with all the heavenly rewards that come with wise management and righteous behavior. In the end, we cut ourselves off from greater blessings in the future when we’re unfaithful to our Master and Provider with today’s smaller stewardship responsibilities.

10“Whoever can be trusted with very little can also be trusted with much, and whoever is dishonest with very little will also be dishonest with much. 11So if you have not been trustworthy in handling worldly wealth, who will trust you with true riches? 12And if you have not been trustworthy with someone else’s property, who will give you property of your own? (vv. 10–12)

Continuing to aim his parable at the Pharisees, Jesus said that if they didn’t use their wrongly obtained wealth for good purposes, by giving to others, they wouldn’t receive redemption and be saved. After all, if they couldn’t be trusted with dishonest riches, they certainly couldn’t be trusted with true riches, such as spiritual life. God doesn’t judge by the magnitude of an act, but by the spiritual principles and motives of each act. A small action may reveal those principles quite as well as a large one might. As we administer the small properties and resources that Father God has entrusted to us here on earth, we’re obligated to become wise in our stewardship responsibilities, as if we owned half the universe.

The “worldly”adjective for wealth, in v. 11, means deceitful, as opposed to true. Worldly riches deceive us by being temporal and transitory, while true riches are eternal, as Apostle Paul emphasizes in 2 Corinthians 4:18. And we’re to be reminded in v. 12 that we’re all God’s stewards and that the perishing possessions of earth aren’t our own (see 1 Chronicles 29:14), however, the resources and gifts that Holy Spirit provides to us are our very own, forever (1 Corinthians 3:22).

In vv. 10–12, Jesus is talking about the stewardship of our God-given resources. He says that if someone is faithful in a small amount, the Lord will entrust him or her with more; but if we’re dishonest in the small things, we’ll likely be untrustworthy and dishonest with the bigger things. And if we’re not “trustworthy with another’s property,” we’re being dishonest in smaller things, and God won’t trust us with big things. In the end, we’ll have cut ourselves off from greater blessings in the future if we’re not faithful in managing today’s smaller things.

“No one can serve two masters. Either you will hate the one and love the other, or you will be devoted to the one and despise the other. You cannot serve both God and money” (v. 13).

Jesus made his final point to the Pharisees in v. 13, shown above. It’s a popular verse that states a concept that isn’t easy for the majority of people to accept. He wanted the Pharisees in particular, but everyone as a whole, including us today, to make a smart decision. They and we cannot concurrently serve or be devoted to both God and wealth! They and we must choose one of the two to prioritize. If God is our Master, then we’re to use our wealth on his behalf. As faithful and just stewards whose one and only Master is God, we’re to utilize such wealth very well as we build up God’s kingdom.

Luke, in chapter 15, highlighted Jesus’ explanation to the Pharisees of why he chose to eat with tax collectors and other “sinners.” Now in chapter 16, he essentially told the Pharisees to repent because they too were sinners. The entire section from 15:1 to 16:15, is about repentance. Therein, Jesus explained to the complaining Pharisees the meaning and importance of repentance and forgiveness, ending his teaching by telling them that they needed to realize their sinful practices and keep from committing them by becoming wise stewards of God’s provisions.

14The Pharisees, who loved money, heard all this and were sneering at Jesus. 15He said to them, “You are the ones who justify yourselves in the eyes of others, but God knows your hearts. What people value highly is detestable in God’s sight (vv. 14–15).

The Pharisees sneered at Jesus (v. 14) after hearing his rebuke of their attitudes and behavior, they derided him with open insolence. Jesus then drove home his point to them in v. 15, telling them bluntly that they continually sought to justify themselves in front of others, appearing to be spiritually elite, despite the fact that God easily saw them as sinners. He admonished their deceitful intentions and behavior, finding everything about them to be detestable, since none of it was godlike or God-honoring, and that their love of money was an abomination to Father God.

How to Approach and Apply This Parable

So why is our shrewd manager deemed to have acted wisely? Even though he was a sinner looking out for his own interests (6:32–34), he models behavior that Jesus’ disciples — then and today — can emulate. Instead of simply being a victim of circumstance, he wisely transformed a bad situation into one that benefited him and others. By reducing other people’s debts, he created a new set of personal relationships based not on the vertical relationship between lenders and debtors but on personal and friendly relationships.

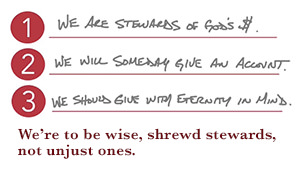

Wise Stewardship The principle that Jesus was trying to convey herein for his listeners then, and his readers today, deals with how we’re to be wise, shrewd stewards, not unjust ones. The unjust steward saw his master’s resources as an opportunity from which to gain. Conversely, Jesus wants those of us who follow him to be obedient, just, and righteous stewards of all that he makes available to us, giving such resources to those in need, according to his will.

Your heart or your loyalty cannot be divided in half! God cannot work with a half-hearted believer. Sadly, your devotion to or fixation on money will automatically take the place of your being fixed on God. It’s impossible to serve two masters concurrently.

If we understand the principle that everything we own is a gift from God, then we should have no difficulty realizing that God owns everything and that we’re to become his wise stewards. As such, we’re to use the Master’s resources to further the Master’s goals. In this specific case, we’re to make a concerted effort to be forever generous with our wealth, using it to benefit others. Jesus teaches a similar concept of helping those in need in his Parable of the Good Samaritan.

Question 1 How do you view your money: (a) “It’s mine, keep your hands off”?; (b) “It belongs to my creditors”? (c) “It’s God’s — I just manage it”? Why? How could you use your money for the sake of the kingdom?

Question 2 Who (or what) are some of the masters you've served in the past? Which masters pull at you for allegiance now? How do you deal with these pressures in light of your commitment to Christ?

“The master commended the dishonest manager because he had acted shrewdly” (Luke 16:8a).

Take our “Parables Quiz.”

See Warren’s other “Parables of Jesus” commentaries.

— Warren’s Concise Summary —

In the Parable of the Shrewd Manager (or Unjust Steward), Jesus tells of a rich man who discovers that his household manager has been wasting his possessions. He then announces that he’ll dismiss him, prompting the manager to fear for his future and devise a plan to secure favor with others, once he loses his job.

Before he’s removed, the manager summons his master’s debtors and immediately reduces the amounts they owe, so that they’ll be inclined to welcome and support him later. The master then surprisingly commends the manager — not for his dishonesty, but for his shrewd foresight — leading Jesus to teach that people should use worldly wealth wisely and faithfully in view of eternal realities, since no one can serve both God and money.