The Lost Sheep, The Lost Coin, The Lost Son

Luke tells us in chapter 15 of his gospel that Jesus told these three parables to a crowd of tax collectors, sinners, Pharisees, and scribes. His teaching brought gospel truth to the tax collectors and sinners — those whose unrighteousness separated them from God — and to the Pharisees and scribes who relied on their own righteous efforts to achieve salvation.

† Find Warren’s short summary at the bottom of page.

The Lost Sheep

The Lost Coin

The Lost Son

Here’s a passionate six-minute portrayal of Jesus telling many his Parable of the Prodigal Son to Pharisees and teachers of the Law.

An excerpt from the “Jesus of Nazareth” film (1977)

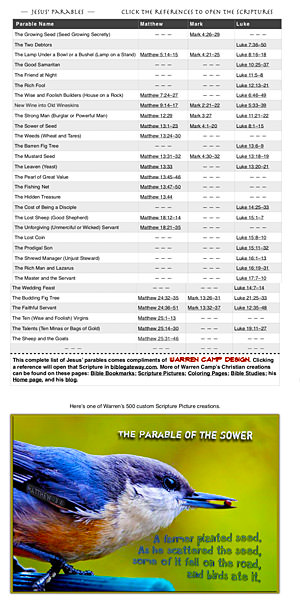

Click the list or the “bird” to enlarge and use Warren’s list of forty-four of Jesus’ parables (a PDF file with links to Scriptures).

Start Reading Warren’s Commentary . . .

Find his summary at the bottom.

par•a•ble [noun] a simple story used to illustrate the meaning of or a moral or spiritual lesson, as told by Jesus in the gospels

synonyms: allegory, moral story/tale, fable

Jesus’ Parables of the Lost Sheep, Lost Coin, Lost Son

Matthew 18:10–14; Luke 15:1–32

Among the 44 or so parables of Jesus (see Warren’s complete list) that are recorded in the three synoptic gospels, there are a good number that are particularly well known because they deal with salvation.

The first two parables — The Lost Sheep and The Lost Coin — set the tone for the third parable: The Lost Son, which is better known as the Parable of the Prodigal Son. The first two parables are similar. In one, when a shepherd loses one sheep, he leaves his flock to find it and rejoices when it’s found. In the second, a woman who lost a silver coin carefully searches her home until she finds it and then invites her neighbors and friends to celebrate with her. Both parables highlight heaven’s rejoicing when each single sinner repents and is found by Lord Jesus.

In Jesus’ third salvation-focused parable, he told a story about two sons. In short, the younger son asked for his inheritance and left home. After he wasted his money on immoral living, he decided to return to his father. Rather than rejecting his wayward son, the father embraced him. The older son, who’d always been obedient to his father, reacted with jealous anger.

Sometimes important principles are repeated in the Bible for emphasis. In response to the chiding from the Pharisees and scribes that Luke details in vv. 1–2 of chapter 15, Jesus spoke three parables that emphasized his response to their rebuke of him. In effect, the Jewish elite had failed to become Israel's true shepherds as God had entrusted them to be. Instead of going out of their way to intentionally seek out Israel's outcasts (lost sheep), they neglected their duties to serve as religious leaders.

In these three “Lost, Lost, Lost” parables, Jesus exemplifies Father God’s heart-felt desire to seek and save all who are lost. All three invite God’s children to sense his great joy when they finally come to their senses, repent, and live lives that please him. When we personalize our relationship with Jesus, our Good Shepherd, and follow him, we who were once lost, lost, lost can now realize and appreciate new life (2 Corinthians 5:17).

The Parable of the Lost Sheep

A Parable of Salvation

Luke 15:1–7 (also in Matthew 18:10–14)

A short, animated video by Superbook

To appreciate the value of this parable, think about the crowd to whom Jesus was speaking. The two opening verses reveal the members of his audience: “But the Pharisees and the teachers of the law muttered, ‘This man welcomes sinners and eats with them.’” The text unlocks the meaning of this first of three salvation-specific parables. Jesus portrayed two groups of people who were in conflict: (1) tax collectors and others who were deemed “sinners,” versus (2) the Pharisees and teachers of the Law (scribes). Such conflict is prevalent throughout the New Testament, especially relating to Jesus’ teaching and life.

Note: The Pharisees grumbled also when Jesus ate with Levi the tax collector (Luke 5:30). And when Jesus stayed at the home of Zacchaeus, the chief tax collector (19:7), we learn that Zacchaeus wasn’t well liked but his interaction with Jesus enabled him to relate personally with Jesus and repent of his wrongdoing. Jesus said to him, “For the Son of Man has come to seek and to save the lost” (v. 10). You might now ask, “Who are ‘the lost’? What does it mean to be lost?” Find both answers below.

Then Jesus told them this parable (v. 3). This first parable is another of Jesus’ great stories, created out of everyday, familiar experiences. Jesus taught the truth about God and his kingdom by using familiar, common, everyday experiences, such as losing a wandering sheep from the herd or losing a coin in one’s house.

“Suppose one of you has a hundred sheep and loses one of them. Does he not leave the ninety-nine in the open country and go after the lost sheep until he finds it? And when he finds it, he joyfully puts it on his shoulders.” (vv. 4–5)

That was common sense for a shepherd: when a sheep lost its way from the flock, its shepherd would immediately leave the remainder of sheep so he could search for and find the lone sheep that became lost. Normally, there’d be several shepherds caring for a flock of sheep; one shepherd would leave to search for the lost sheep while the other shepherds watched over the remaining flock. Verse 4 especially amounts to an invitation for Christians to search for and locate those persons who’ve wandered or become lost from a faith-filled life.

Verse 5 is a pivotal moment in the Parable of the Lost Sheep, where Jesus describes a shepherd’s reaction after successfully finding a sheep that had wandered away. While the verse seems simple, it contains deep theological and cultural layers about how God views and treats those who are “lost.” It’s also worth noting that this image of the shepherd with a sheep on his shoulders was one of the earliest symbols of Christianity — found in the Roman catacombs long before the cross became the primary symbol of the faith. It represented Jesus as the “Good Shepherd” who personally carries his people.

A 2-minute, animated video about the Lost Sheep Parable by RodTheNey

The Parable of the Lost Coin

Another Parable of Salvation

Another short, animated video with musical accompaniment

Jesus addressed this second salvation-focused parable directly to the Pharisees who were lost but didn’t think they were.

“Or suppose a woman has ten silver coins and loses one. Does she not light a lamp, sweep the house and search carefully until she finds it?” (v. 8)

The first word “Or” in v. 8 connects this parable to the previous one. Both use the same theme having a focused diligence to find something that’s become lost, as we see that the woman householder and the good shepherd both searched for what was precious, yet lost to them.

“And when she finds it, she calls her friends and neighbors together and says, ‘Rejoice with me: I have found my lost coin’” (v. 9).

The woman was joyful in her heart that she’d found what was lost. The ten silver coins refer to a piece of jewelry, having ten silver coins on it, which was worn by brides. This was the equivalent of a wedding ring in modern times. This is what makes the parables of Jesus so meaningful: They express a universal experience for all people, regardless of century or culture. So it is with God, when someone who’s lost his or her senses about God finds their way back to him.

“In the same way, I tell you, there is rejoicing in the presence of the angels of God over one sinner who repents” (v. 10).

In v. 10, Jesus is telling us how happy and joyful God and his angels in heaven are when the lost — those who’ve yet to personally meet Jesus and choose him to become their Lord — are finally found when they come to their senses and return to God and his righteous ways. Again, the context unlocks the meaning of the parable. The “lost” in this parable’s audience are the Pharisees and teachers of the Law. Jesus wanted these religious leaders to understand how he felt about those who were lost. Each sinner is special to God; there’s rejoicing in heaven when “each one” repents. In our world, the “lost” are those who haven’t yet begun to believe in and follow Christ Jesus.

In this parable, once the woman found her coin, she called her friends and neighbors so they could share her good news. Today, when a sinner is restored to fellowship with God, it’s a cause for rejoicing.

The Parable of the Lost Son

A Parable of Salvation

The Parable of the Lost (or Prodigal) Son is one of the greatest love stories ever told: a story filled with mercy and grace. It’s a parable of how God views us and how we can choose to repent and turn to God or reject him. It’s about a father and two sons. While the older son stayed home and worked hard for his father, the younger son ran away with his inheritance and spent it on foolish things (as the video below highlights). Finding himself alone, working as a slave so that he could be fed, and having to live with pigs, the younger son returned home, hoping to again be able to work for his father. Thankfully, the father welcomed home his son with open arms and heartfelt compassion. The older son became very angry about his brother having returned home and about his father’s agreement to warmly accept his brother’s return home.

The key word in the first two parables is “repent.” Both are an invitation for listeners and readers — them and us — to repent and return to prioritizing God in our lives. This third parable illustrates the meaning of repentance. And the major theme of this parable doesn’t seem to be so much the conversion of the sinner, as in the previous two parables, but rather the restoration of a believer into fellowship with the Father. In the first two parables, the owner went out to look for what was lost, while in this story the father waited patiently and watched eagerly for his son’s return. You’ll see in this story’s video depiction the graciousness of the father, overshadowing the sinfulness of the son, with the memory of the father’s goodness being what brought the prodigal son to repentance.

A 3-minute dramatization narrative (NIV)

Many people feel that the Parable of the Lost Son (or Prodigal Son) is the priceless pearl of Jesus’ parables. It’s his finest, most sensitive parable, the most valuable story he ever presented. Charles Dickens, the great English author, called this one parable “the greatest story ever told.”

This parable is about a son who rebelled, then remembered. This presentation of a wayward son illustrates a sinner’s separation from God, followed by that sinner’s repentance and God’s restoration of him or her. It follows very well the close of the second parable (v. 10), which reads: “I say to you, there is joy in the presence of the angels of God over one sinner who repents.” Jesus’ heartwarming story illustrates how a sinner can remember his Father (with a capital “F”), return to him, repent of his or her sinful ways, and be restored. The parable’s turning point was when the son remembered his father and realized the value and importance of what his father had continually provided. Of course he could have — and should have — remembered and returned sooner, however, the personal account shows us well that it’s never too late to remember our Father and return to him, for he waits very patiently for the return of wayward, distracted souls.

Jesus continued, “There was a man who had two sons. 12The younger one said to his father, ‘Father, give me my share of the estate.’ So he divided his property between them” (vv. 11–12).

It seems that in Jesus’ parables we often find two or more people, sometimes sons, which is symbolic of two alternative ways to live. (See my summaries of the Parables of the Two Sons, Pharisee and the Tax Collector, Wise and Foolish Builders, Two Debtors, Wheat and Weeds, Wicked Trustees, and Rich Man and Lazarus.)

Let’s unfold the meaning of this parable by starting at v. 12, in which the younger son asked his father for his share of his estate, which would have been half of what his older brother would receive; in other words, 1/3 for the younger, 2/3 for the older (see this law in Deuteronomy 21:17). Though it was perfectly within his rights to ask prematurely for his inheritance, it wasn’t a loving thing to do; it implied that he wished his father dead. However, instead of rebuking his son, the father patiently granted his request. This son learned the hard way that covetousness leads to a life of dissatisfaction and disappointment. He also learned that the most valuable things in life are those that you cannot buy or replace.

“Not long after that, the younger son got together all he had, set off for a distant country and there squandered his wealth in wild living. 14After he had spent everything, there was a severe famine in that whole country, and he began to be in need. 15So he went and hired himself out to a citizen of that country, who sent him to his fields to feed pigs. 16He longed to fill his stomach with the pods that the pigs were eating, but no one gave him anything” (vv. 13–16).

Note in v. 13, above, that the younger son traveled to a distant country. Evident from his previous actions, he’d already made that journey in his heart; his physical departure was a display of his willful disobedience to all the goodness that his father had offered him. In the process, he squandered everything that he’d been given. His financial disaster was followed by a natural disaster — a famine for which he’d failed to plan. So he sold himself into physical slavery to a non-Jewish Gentile, finding himself feeding pigs, which was a detestable job to him since he was a Jew. He must have been incredibly desperate at that point to willingly enter into such a loathsome position.

“When he came to his senses, he said, ‘How many of my father’s hired servants have food to spare, and here I am starving to death! 18I will set out and go back to my father and say to him: Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you. 19I am no longer worthy to be called your son; make me like one of your hired servants.’ 20So he got up and went to his father” (vv. 17–20a).

As you see in the passage and the video above, the son began to reflect on his condition. He realized that even his father’s servants lived better than he did. Fortunately, his painful circumstances helped him see his father in a new light that brought him hope. Such a change of heart is reflective of the sinner when he or she discovers the destitute condition of his or her life because of sin. It’s a realization that, apart from God, there’s no hope. So the son devised a plan of action. He realized he had no right to claim a blessing upon returning to his father’s household, nor did he have anything to offer, except a life of service, in repentance of his previous actions. With that, he was prepared to fall at his father’s feet and hope for forgiveness and mercy.

“But while he was still a long way off, his father saw him and was filled with compassion for him; he ran to his son, threw his arms around him and kissed him” (v. 20b).

Jesus next portrays the father as waiting for his son. Perhaps he’d searched the distant road daily, longing for his appearance. Finally, the father noticed him while he was still a long way off. The father’s expressed compassion assumes some knowledge of the son’s pitiful state. In those days, it wasn’t the custom of men to run; yet the father lifted his robe and ran to greet his son (v. 20b). Why would he break convention for this wayward child who’d sinned against him? . . . It’s obvious: He loved his son and was eager to reveal that love and restore their relationship.

The father was so filled with joy at his son’s return that he didn’t even let him finish his confession. Nor did he question or lecture him; instead, he unconditionally forgave him and accepted him back into fellowship. The father running to his son, greeting him with a kiss, and ordering a celebration is a picture of how our heavenly Father feels towards sinners who repent. God greatly loves us and patiently waits for us to repent so he can show us his generous mercy because he doesn’t want anyone to perish.

“The son said to him, ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven and against you. I am no longer worthy to be called your son.’

22“But the father said to his servants, ‘Quick! Bring the best robe and put it on him. Put a ring on his finger and sandals on his feet. 23Bring the fattened calf and kill it. Let’s have a feast and celebrate. 24For this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found.’ So they began to celebrate” (vv. 21–24).

The wayward son who’d returned to the father was satisfied to return home as a slave. But to his surprise and delight, he was restored, receiving the full privilege of being his father’s son. He’d been transformed from a state of destitution to complete restoration. That's what God’s grace does for penitent sinners.

The father then ordered his servants to bring the best robe (a sign of dignity and honor, proof of the prodigal’s acceptance back into the family), a ring for the son’s hand (a sign of authority and sonship), and sandals for his feet (a sign of not being a servant, since servants didn’t wear shoes or, for that matter, rings or expensive clothing). This wasn’t simply a party; it was a rare, complete celebration. Had the boy been dealt with according to the Law, there’d have been a funeral, not a celebration. Instead of condemnation, there was rejoicing for a son who’d been dead but had come back to life, who once was lost but had been found.

“Meanwhile, the older son was in the field. When he came near the house, he heard music and dancing. 26So he called one of the servants and asked him what was going on. 27‘Your brother has come,’ he replied, ‘and your father has killed the fattened calf because he has him back safe and sound.’

28“The older brother became angry and refused to go in. So his father went out and pleaded with him. 29But he answered his father, ‘Look! All these years I’ve been slaving for you and never disobeyed your orders. Yet you never gave me even a young goat so I could celebrate with my friends. 30But when this son of yours who has squandered your property with prostitutes comes home, you kill the fattened calf for him!’” (vv. 25–30)

We come to the final and tragic character in the Parable of the Lost (or Prodigal) Son, the older son, who illustrates the Pharisees and scribes. Outwardly they lived blameless lives; inwardly their attitudes were abominable (Matthew 23:25–28). This was true of the older son who worked hard, obeyed his father, and brought no disgrace to his family or townspeople. Think about the crowd to whom Jesus was speaking. Readers of this parable often focus on the younger son — the one with whom the tax collectors and sinners could identify — but Jesus also made a point about the older son: He was like the Pharisees and scribes who focused on their own morality; he felt entitled to his father’s favor.

Upon his brother’s return, the older brother’s words and actions demonstrated that he wasn’t showing love for his father or brother. In those days, one of the duties of an eldest son would have included reconciling disputes between the father and his son. He was to have been the host at the feast that celebrated his brother’s return. Yet he remained in the field instead of inside the home.

“‘My son,’ the father said, ‘you are always with me, and everything I have is yours. 32But we had to celebrate and be glad, because this brother of yours was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found’” (vv. 31–32).

The older son’s behavior would have brought public disgrace upon the father. Nevertheless, the father, with great patience, approached his angry and hurting son. He didn’t rebuke him, as his actions and disrespectful address of his father warranted, nor did his compassion cease when he listened to his complaints and criticisms. The boy appealed to his father’s righteousness by proudly proclaiming his self-righteousness in comparison to his brother’s sinfulness.

Sadly, by saying, “This son of yours,” the older brother avoided acknowledging the fact that the prodigal was his brother (v. 30). Similar to the Pharisees, the older brother defined sin by outward actions, not inward attitudes. He was saying that he was the one worthy of that celebration and his father had been ungrateful for all his work.

It was the younger brother who’d squandered his wealth; it was he who was getting what the older son deserved. Note: The father tenderly addressed his older boy as “My son” (v. 31), correcting the error in the older son’s thinking by referring to the wayward son as “this brother of yours” (v. 32). The father’s response, “We had to celebrate.” Therein, the father calmly gives his older son reasons rather than shaming him for his anger. He, too, suggests that the older brother was obliged to join in the celebration.

And it was the older brother who focused on himself; as a result, there was no joy in his brother’s return home. He was so consumed with issues of justice and equity that he failed to see the value of his brother’s repentance and return. He chose suffering and isolation over restoration and reconciliation. He resembled the Pharisees and religious leaders who were irate when Jesus received and forgave “unholy” people; he too failed to see his own need for a Savior. Jesus taught people that he was the Son of God. He sought sinners who’d wandered far from him and those who’d tried to earn salvation by their good works.

When we understand that a parable is an imaginary story to illustrate a spiritual point, we can quickly perceive that Jesus was using this account to teach the Pharisees, and all of us, about God the Father’s love for each of us. And while we are all sinners, it’s heartwarming, comforting, and, yes, almost incomprehensible that God the Father is always willing to accept our sincere return to him, given the mistakes we’ve made.

If we're lost spiritually, let's look for the familiar way home that God has provided us. He points us toward his loving light and to where we’re supposed to be. Compassionate God: Please help me turn from the darkness of being lost, so I’ll be better able to return to your light and love. Many thanks, Lord.

A 5-minute, animated video about the Lost Son Parable by RodTheNey

How to Apply This “Running Back to God” Parable

Jesus' prodigal-son story is probably the best known of his parables. Perhaps we love it so much because we can find ourselves in the narrative, since we’ve all moved out of our Father’s will at one time or another. When we reject God’s will, we enter what the King James Bible calls a “far country,” even if we never leave our hometown. Satan beckons with promises of new experiences and entertainment, whispering to us, Come satisfy your curiosity — this is the way to really live. But the reality of the “far country” doesn’t fulfill those empty promises. Sin distorts our thinking, causing us to lose our sense of what’s right and good. We squander time, money, and relationships. Our God-given talents, ambitions, and opportunities are wasted on pointless pursuits as we pour days and dollars into things that bring only temporary satisfaction.

Outside of God’s will, it’s easy to make foolish decisions and end up in trouble. That could involve some physical or financial need. Or it might even be a wretched emotional state, in which we feel isolated, unloved, or rejected.

The ultimate end to such a journey is our personal “hog pen” — the place where we finally realize that sin doesn’t pay. Having traveled so far to reach this new low, we may wonder if the Lord can ever love us again. The answer is yes. Our sin can never outdistance the reach of God’s grace. If we, like the prodigal son, will turn around, repent, and come home to the Father, we’ll receive his restoring forgiveness and be welcomed home with rejoicing.

Seeing clearly the picture of the father receiving the son back into a familial relationship ought to remind us also of how we, having once been lost, should respond to repentant sinners. It’s only by God’s grace that we and others can be saved and have become saved. That’s the take-away message of the Parable of the Lost (or Prodigal) Son.

Question 1 Have you ever strayed from the Christian faith? How did God bring you back?

Question 2 How do these three “lost” stories make you feel about your value to God?

Question 3 How could these stories affect your relationships with those you know who wander from the faith?

“‘For this son of mine was dead and is alive again; he was lost and is found.’ So they began to celebrate” (Luke 15:24).

Take our “Parables Quiz.”

See Warren’s other “Parables of Jesus” commentaries.

— Warren’s Concise Summary —

Jesus’ three parables — the Lost Coin, Lost Sheep, and Lost Son — teach that God deeply values those who are lost and he rejoices when they are found. In these stories, a shepherd leaves ninety-nine sheep to find one that wandered off, a woman diligently searches for her missing coin, and a father welcomes back his repentant son who’d gone astray.

Each parable shows God’s relentless love and the great joy in heaven over every sinner who repents and restores his relationship with him.