The Parable of the Good Samaritan differs from most other parables: It’s so simple and concrete that a child can understand its basic point.

This parable makes clear who our neighbor is and how we should respond to his or her needs.

— Preview —

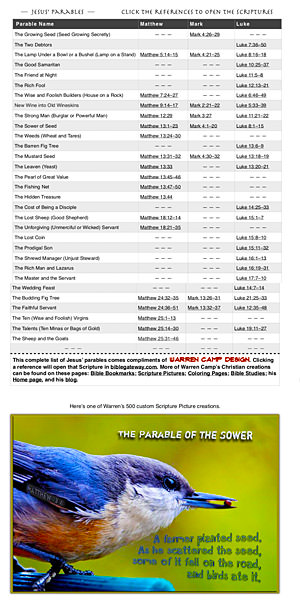

Click the list or the “bird” to enlarge and use Warren’s list of forty-four of Jesus’ parables (a PDF file with links to Scriptures).

Watch this popular JESUS film clip about the Parable of the Good Samaritan.

par•a•ble [noun] a simple story used to illustrate the meaning of or a moral or spiritual lesson, as told by Jesus in the gospels

synonyms: allegory, moral story/tale, fable

Jesus’ Parable of the Good Samaritan

Luke 10:25–37

Found only in Luke’s gospel, the Parable of the Good Samaritan differs from most other parables. It’s so simple and concrete that a child can understand its basic point. However, it’s also an insightful and memorable assessment of practical moral principles. So many believers and non-believers, understand it. That shows the effectiveness of its simplicity and depth.

The good Samaritan was a man who helped a badly injured Jew, even though Jews looked down on Samaritans. Perhaps surprisingly, a priest and a Levite walked passed that man despite the urgent need for help. In this story, the Samaritan looked past the day’s social norms and stepped out and helped a person who might otherwise have insulted or abused him. Jesus’ parable message makes it clear that everyone is our neighbor. As a result, we should help and aid fellow man — regardless of whether he or she looks like us, lives near us, believes what we believe, is of a similar social standing, and so on.

Jesus’ story primarily involves four anonymous men: one man who’d been attacked, robbed, and beaten by thieves; two other men, passersby, who had opportunities to minister to and rescue the injured man; and another man from Samaria who happened on the scene. The Jews of Jesus’ day had a very negative perception of Samaritans. When Jesus included a Samaritan character in his parable to contrast the typical behavior pattern of Israel’s spiritually elite, the Israelites became incensed and viewed Jesus as being extremely counter-cultural. Jesus saw the need to tell this parable to the Jews in response to one of their lawyers asking him, “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” and “Who is my neighbor?”

The Parable of the Good Samaritan

A Parable of Christian Life

A 5-minute depiction of the Lord Jesus’ Parable of the Good Samaritan

The Parable of the Good Samaritan

25On one occasion an expert in the law stood up to test Jesus. “Teacher,” he asked, “what must I do to inherit eternal life?”

26“What is written in the Law?” he replied. “How do you read it?” (Luke 10:25–26)

The Parable of the Good Samaritan is among the handful of Jesus’ stories that, whether or not you’re a church-going person, you can likely recount from memory. “Being a Good Samaritan” has become cultural shorthand for showing kindness and assisting those who are less fortunate. But Jesus’ story is far more unsettling than a fable encapsulating principles to spur common decency.

In Luke 10, this parable provides not so much a moral tale for us to dissect, but a story in which we live. It stretches our imagination, inviting us to: walk that treacherous road through dangerous country; know the threat of armed hooligans at every blind bend; sense conflict over how to engage our religious convictions in complicated situations; struggle over what exactly it means to love our neighbor; and grapple with how Jesus embodies reckless love.

When one of Israel’s religious experts tried to trap Jesus inside a tightly spun web of theological intricacies, Jesus reversed the interrogation: How do you understand the essence of God’s law? With his tactical examination careening out of control, the exasperated questioner found himself uttering the very words Jesus had quoted from Deuteronomy, as the greatest of all the commandments and the heart of everything Scripture teaches: “‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind’; and, ‘Love your neighbor as yourself’” (Luke 10:27).

You’ve nailed it, Jesus said. Go do that.

Feverishly scrambling to regain the upper hand, the religious expert had a burst of inspiration and devised one last conundrum. I’d be happy to, he answered, sitting back smugly, if only you could tell me who among all the masses is actually my neighbor. Without batting an eye, Jesus launched into his compelling story.

Again, Jesus spoke in a parable, this time to Jewish teachers of the Law of Moses. While such teachers were expert in Mosaic Law (the Greek nomikós, “learned in the Law”), they weren’t at all like the court lawyers that we see today. One such man, a scribe or expert in the Law, asked Jesus a question: “Teacher, what must I do to live forever?” (v. 25). His question provided Jesus with an opportunity to define what his listening lawyers’ relationship should be to their neighbors. The text says that a lawyer (a scribe) had put the question to Jesus as a test, but the text doesn’t indicate that there was hostility in the question. He could simply have been seeking information.

He knew that this lawyer was an expert in God’s Old Testament laws so, instead of answering the question, he shot back his own question (which was a common way that Jesus responded to people’s questions; we call that the Socratic Method). He asked the man, “What is written in the Law?” and “How do you read it?” By referring to the Law, Jesus was directing the man to an authority they’d both accepted as truth: the Old Testament. In essence, he was asking the scribe what Scripture said about this and how he interpreted that Scripture. Jesus thereby avoided an argument while giving himself the opportunity to evaluate the scribe’s answer, instead of the scribe evaluating Jesus’ answer. The scribe answered Jesus’ question by quoting Deuteronomy 6:5 and Leviticus 19:18.

27He answered, “‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind’; and, ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’”

28“You have answered correctly,” Jesus replied. “Do this and you will live” (vv. 27–28).

The lawyer answered correctly: “‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind’ and, ‘Love your neighbor as yourself’” (v. 27). In the next verse, Jesus told the man that he answered correctly. That was, indeed, the greatest commandment, and that obeying it would enable someone to live forever. Jesus then told the scribe that he’d given an orthodox (scripturally proper) answer, but went on in v. 28 to tell him that such love required more than an emotional feeling; it was to also include orthodox practice, which would have required him to “practice what he preached.”

The scribe was an educated man; he realized that he couldn’t possibly keep that law, neither would he have necessarily wanted to keep it. There would always be people in his life that he’d be unable to love. Thus, he tried to limit the law’s command by limiting its parameters. He therefore asked his follow-up question to justify himself: “Who is my neighbor?” (v. 29)

The lawyer subsequently asked what specifically he might need to do to love his neighbor as himself. By asking “Who is my neighbor?” he wanted to know if he had to love every one of his neighbors or just the ones who lived close to him. Instead of telling the teacher of the Law the correct answer, Jesus told him his Good Samaritan Parable, which I’ll detail beneath the text of vv. 30–35.

30In reply Jesus said: “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, when he was attacked by robbers. They stripped him of his clothes, beat him and went away, leaving him half dead. 31A priest happened to be going down the same road, and when he saw the man, he passed by on the other side. 32So too, a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. 33But a Samaritan, as he traveled, came where the man was; and when he saw him, he took pity on him. 34He went to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring on oil and wine. Then he put the man on his own donkey, brought him to an inn and took care of him. 35The next day he took out two denarii and gave them to the innkeeper. ‘Look after him,’ he said, ‘and when I return, I will reimburse you for any extra expense you may have’ (vv. 30–35).

To be clear, this wasn’t an actual event. However, it’s believable because it could easily have happened. The distance from Jerusalem to Jericho is about 16 miles (or 26 kilometers). A familiar, often-traversed road ran through desolate mountain ravines without any habitation, save the inn. It provided places for robbers to hide and conduct surprise attacks on people commuting there with their livestock and possessions. In v. 30, Jesus tells us that a traveler had been robbed and wounded, using the Greek word plege. It means “to smite, to hit, to wound,” or “to violently strike.” Notice by using plege, Luke wanted his readers to appreciate that the man’s wounds were so devastating that when the thieves departed, they assumed he was dead. These were mortal wounds. The video above depicts the terrain and the man’s wounds extremely realistically.

The Greek word for “neighbor” — rey’a — means “someone who is near or close to.” In the Hebrew it means someone with whom you have an association. It would have interpreted “neighbor” in a limited sense, thereby excluding Samaritans, Romans, and other foreigners. Jesus then told his Parable of the Good Samaritan to correct the false understanding that the scribe had of who his neighbor might be and what his duties were to his neighbor.

The Priest The Jewish lawyers who were listening to Jesus tell this parable would have been able to relate to the troublesome situation in which the man in the parable was found. In v. 31, we read that a priest was going down that roadway, which would have been a very natural thing for a priest to do, for there was then a very large priestly settlement at Jericho. It would have been a significant relief for the wounded man to have had a Jewish priest approach, take pity on, and aid him. After all, priests were God’s helpers in the temple; they knew how to worship God; they knew and could recite from memory all of God’s rules. But, sadly for the wounded man in the parable, the priest passed by without offering a hint of care or assistance.

The Levite Down the roadway came another Jew: a Levite (a temple minister who was revered in the eyes of the Israelites as being fully righteous; the tribe of Levi had been set apart by God for his service). He also came upon the injured man; he too had the opportunity to see if he could be of help. Alas, having also been expected to stop and help, the Levite saw the man and intentionally walked right past him. He avoided getting involved with the near-dead man. There may have been a variety of excuses for his neglect of the wounded man: danger, hate, dread of defilement, expense, and so on, but Jesus didn’t consider any of them worth mentioning.

The Samaritan This Jewish audience would have expected Jews to help a human being who’d been harmed and was in obvious need. What they didn’t expect was what Jesus said next. He told them in his parable that it wasn’t a Jew who eventually helped the injured man — it was a Samaritan — someone not likely in the eyes of the Israelites to show compassion for an injured person, as the Law commanded them to do. The Jewish lawyers who were listening to Jesus tell his parable were in disbelief when they heard Jesus say that this Samaritan was good, that he saw and approached the severely wounded man, and that he intentionally helped him.

Incidentally, Jews considered people from Samaria as a low class of people since they’d intermarried with non-Jews and didn’t keep all the Laws of Moses; they saw Samaritans as half-breeds who weren’t true Jews. We can see what brought about such prejudice by reading 2 Kings 17:24–41. When the Jews of the northern kingdom were taken captive by the King of Assyria, they attempted to resettle themselves in Samaria and began to intermix with the Assyrian people. Such intermarriages were prohibited throughout the Old Testament laws.

Nevertheless, Jesus demonstrated in his parable that it was a Samaritan who’d taken extraordinary measures to help the wounded man. We don’t know if the injured man was a Jew or non-Jew, however, it made no difference to the Samaritan; he didn’t consider the man’s race or religion. He not only provided the man with immediate aid by applying oil (to sooth the pain) and wine (to disinfect the man’s wounds), since both fluids were used as medicine in those times.

He also involved himself very personally in the man’s dire situation by doing the following: First, he lifted the man onto his donkey and took him to a nearby inn; he spent the night taking care of the man’s specific needs; he thoughtfully and proactively paid the innkeeper to take care of the man until he became well. The next morning, the Samaritan had to leave to continue on his journey. Incidentally, the two silver denarii coins that the Samaritan had given to the innkeeper would have been equal to two days’ wages, which would have covered his staying for up to two months in an inn. He even told the innkeeper that he’d return, the next time he was traveling there, and pay more money if the man still needed medical care and lodging.

36“Which of these three do you think was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?” (v. 36)

The lawyers who’d heard Jesus’ account were very surprised to hear how this parable ended. When Jesus finished speaking, he asked the expert in the Law this question: “Which of these three do you think was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?” The expert in the law replied, “The one who had mercy on him,” albeit the Samaritan. Because the good man was a Samaritan, Jesus had drawn a strong contrast between those who “knew the Law” and those who actually “followed the Law in their lifestyle and conduct.” Jesus then asked the lawyer if he could apply the lesson to his own life by asking him, “Which of these three do you think was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of robbers?" (v. 36).

The expert in the law replied, “The one who had mercy on him.”

Jesus told him, “Go and do likewise” (v. 37).

Once again, the lawyer’s answer revealed his personal hardness of heart. Instead of answering didactically, “Everybody is your neighbor,” Jesus had embodied the law of neighborliness in the good Samaritan, making it so beautiful that the lawyer had difficulty commending it. He was unable to bring himself to say the word “Samaritan” because that word was so distasteful to his lips. Instead, he made reference only to “The one who had mercy on him.” His obvious hate for Samaritans (his neighbors) was so strong that he couldn’t even refer to them appropriately. In the end, Jesus told the lawyer, “Go and do likewise,” meaning that he should start living what the Law had been telling him to do.

The priest and the Levite didn’t love this parable’s “stranger in need” the way the Samaritan did. The Samaritan was the only person who, by his actions, considered the wounded man to be his neighbor. The message Jesus communicates herein is this: The meaning of “Love your neighbor as yourself” is that people are to show mercy and kindness to anyone and everyone as needed. The Samaritan and wounded man were neighbors because both were humans in need and both had been created in God’s image (Genesis 1:27).

A Hearty Way to Approach and Apply This Parable

No doubt we’d all like to to identify with the Good Samaritan, but in reality, we often find ourselves responding more like the priest or the Levite. We aren’t told explicitly why neither stopped to help the man in need but can deduce the answer by comparing their actions with the Samaritan’s: He saw with eyes of compassion; his compassion led him to seize the opportunity to help; and he willingly shared what he had.

Is it possible you’ve missed seeing the needs around you and your neighborhood? Ask the Lord to open your eyes and give you his active compassion for those who hurt. We Christians, today, are to love our neighbor as we love ourselves. To be clear, a neighbor isn’t only a person who lives near us or is in our circle of friends. A neighbor is a person, a human, who, no matter where he or she lives or what she or he believes, has personal needs. We should make the effort to learn of those specific needs and determine how we can help meet those needs lovingly.

By concluding his parable as he did, Jesus is telling us today that we’re to follow the Samaritan’s example in our own conduct. We’re obliged to show compassion and love for those we encounter in our everyday activities who struggle to meet their needs. We are to love others (v. 27) regardless of their race or religion; the criterion is need. When we see and appreciate their need and realize that we have the ability to meet one or more of those needs, we’re to give generously and freely, without expectation of return.

We ought now to conclude that the Parable of the Good Samaritan was taught, then and now, simply as a lesson on what it means to love one’s neighbor.

Question 1 What attitude or behavior does God want you to have that’s the most difficult to accept?

Question 2 Imagine being a Good Samaritan to someone need? Commit to making the effort to “love your neighbor as yourself.”

Jesus told him, “Go and do likewise” (Luke 10:37b).