2 Samuel 12:1–14 . . . Bible Study Summary with Videos and Questions

“Nathan Rebukes David”

Today we’ll see the results of sin in David’s life, beginning in Chapter 12. We’re told that when Nathan came with his announcement, “You are the man!” he told David (v. 7): “. . . because you despised me and took the wife of Uriah the Hittite to be your own (v. 10),… the Lord says, ‘Out of your own household I am going to bring calamity on you’ (v. 11). But because by doing this you have shown utter contempt for the Lord, the son born to you will die” (v. 14). Nathan’s declared prophecy to David would literally be fulfilled by Absalom, David’s son (as documented here).

This is a great lesson in forgiveness. A lot of people today ask God to forgive their sins; they think, thereafter, that they needn’t suffer due to their evil ways. But notice what God will do with David; he’ll forgive him after he confesses. David’s life will be spared, even though under the Law the penalty for his sin was death. God will forgive David, thereby restoring their inner-personal relationship so that David will have a sense of peace and freedom from guilt.

It would be helpful to read David’s humble “prayer of a contrite sinner” for forgiveness, cleansing, and purity of heart, which appears in Psalm 51:10 <Click to read the verse.)

[Note: Click the link to This Week’s Passage near the bottom of this page to read today’s Scripture.]

Nathan Tells David a Sheep Parable (2 Samuel 12:1–6)

The “man after God’s own heart” had fallen and become hardened to God’s voice. How would God restore him? “The LORD sent Nathan to David” (v. 1a). David’s sin displeased the LORD because David wouldn’t listen to the conviction of the Holy Spirit or to his conscience. As a result, God sent someone else to speak directly to David. Praise God that his servants can hear the voice of the LORD and respond to Him!

To David, God sent Nathan the prophet who knew what David had just done to Bathsheba and Uriah. Pardon the pun, but David the shepherd, couldn’t pull the wool over Nathan’s eyes. His words were, in the final analysis, God’s very words (see v. 11). He had an extremely sensitive assignment: to help David repent of his sins without making him defensive and shutting off communication. It’s hard enough to reason about such a sensitive subject with a normal man or woman, but a king had supreme authority and didn’t have to listen to people who annoyed him. So Nathan chose to tell David a story, something of a “judgment parable” under divine inspiration. On the surface it was a story that might have come from a local court. As king, David would often be asked to decide difficult civil cases such as this. So, with his judge hat on, David listened — not realizing that Nathan’s parable mirrored his own sin!

Nathan’s parable begins: “There were two men in one city.” With wisdom and courage, he used a story to get the message through to David. It was common in those days to keep a lamb as a pet. Nathan used this pet lamb story to speak to David, his friend. Previously Prophet Nathan delivered a message of great blessing to David (1 Samuel 7). David knew that Nathan wasn’t a negative critic but a friend, so he was receptive to the parable’s message. The sin that Nathan cites in v. 4b of his parable — “Instead, he took the ewe lamb that belonged to the poor man” — was theft. There’s a sense in which David stole something from Uriah. The Bible says that, in marriage, a husband has authority over the body of his wife (and vice-versa). Obviously David didn’t have such authority over Bathsheba’s body, which he stole from Uriah. Adultery and sexual immorality are definitely theft!

You might see Nathan’s telling David this sheep-related parable as a skillfully employed tactic that gets David to pronounce judgment on a crime before realizing that he himself was the criminal. David was angry at the “rich man’s” lack of compassion. If he could, he’d have had that ruthless sort put to death.

In his parable, Nathan revealed important comparisons: The rich man (David), who had numerous cattle (wives), took the only lamb (Bathsheba) of the poor man (Uriah)… Most sensitively, David responded by declaring his obvious judgment, without realizing that in it, he was judging himself.

Let’s give this parable some background. David had become king of both Judah and Israel, taking the city of Jebus, renaming it “Jerusalem” and making it his capital city. He’d built his palace and given thought to building a temple. He’d subjected most of Israel’s neighboring nations. But the Ammonites had retreated to the royal city of Rabbah, and as the time for war (spring) approached, David sent all Israel, led by Joab, to besiege the city to bring about its surrender. David chose not to endure the rigors of camping in the open field, outside the city, but to remain in Jerusalem. Sleeping late, David rose from bed one night when others actually go to bed. He strolled on his palace rooftop and happened to see a beautiful young woman bathing herself, perhaps ceremonially, in fulfillment of the law. [Read the full account that's detailed in last week's summary.]

In vv. 5–6, David condemns the cruel man in Nathan’s parable. His anger was greatly aroused. Nathan didn’t ask David for a judicial decision, and David naturally assumed the story was true, immediately passing sentence on the story’s guilty man. David’s action ought to remind us that we often try to rid our guilty consciences by passing judgment on others. David, burning with anger against the rich man, told Nathan in v. 5b, “the man who did this must die!” David’s sense of righteous indignation was so affected by his own guilt that he commanded a death sentence for the hypothetical case brought by Nathan, even though there was no capital offense.

David’s use of the oath “As surely as the Lord lives” shows how passionate his indignation was. He called on God to witness the righteousness of his death sentence upon Nathan’s hypothetical rich man. David continued with his sentence by demanding that the man “pay for that lamb four times over, because he did such a thing and had no pity” (v. 6). David rightly knew that penalizing the rich man — even with a death sentence — wasn’t enough. He also felt the need to fully restore to the poor man what had been taken from him. He knew that true repentance meant restitution. The “four times over” reference also shows that David’s sin and hardness of heart didn’t compromise his knowledge of Scriptures. He immediately knew what the Bible said about those who steal sheep: “Whoever steals an ox or a sheep and slaughters it or sells it must pay back five head of cattle for the ox and four sheep for the sheep” (Exodus 22:1). David knew the words of the Torah but was distant from its Author.

David’s statement in v. 6 ends with “because he did such a thing and had no pity.” The idea is that the rich man should have had pity on his neighbor but didn’t. In the same way, David should have had pity on Uriah and Bathsheba’s father and grandfather but didn’t.

Nathan’s parable was meant to expose David’s sin so that it couldn’t be denied. Having done that successfully, he then pressed on to deal with David’s specific sins.

Nathan Indicts David as the Culprit (vv. 7–12)

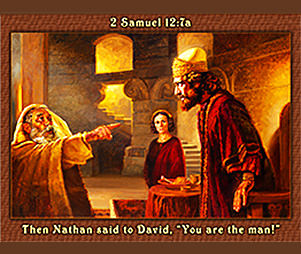

No sooner had David stated his judgment of the rich man in the parable, Nathan nailed him. David had sprung the trap on himself, and Nathan was about to let him know the details. The first thing he did was to dramatically indict David as the culprit: “You are the man!” In stunned silence, David listened to the charges against him. He probably thought only in terms of the evils that the rich man committed against his neighbor, stealing a man’s sheep and depriving him of his loved companion.

Put another way, David focused more on the rich man’s socially unacceptable behavior, instead of sinful acts. In vv. 7–12, Nathan draws David’s attention to his sin against God and the consequences God has pronounced for such sin.

The real point of Nathan’s parable is this. We hear his rebuke as though David’s sin was all about sex. [Not!] David did commit a sexual sin by taking Bathsheba and sleeping with her, knowing she was a married woman. But this sexual sin is symptomatic, according to Nathan (and God). God wasn’t simply saying, Shame on you, David! Look at all the wives and concubines you had to sleep with. If none of them pleased you, you could have chosen another, just one that wasn’t already married.

As Nathan told David the story of a rich man and a poor man, God told David (through Nathan) that He’d given to him all that he possessed (his riches) and would add even more riches. David’s problem was that his possessions had come to own him. He was so “possessed” with his riches that he was unwilling to utilize or spend any of them. He wanted more and began to take what wasn’t his to take. He should have first conferred with the divine Giver.

Following the text in vv. 7–8, in which Nathan reiterates God’s words, “I anointed you king over Israel, and I delivered you from the hand of Saul. I gave your master’s house to you, and your master’s wives into your arms. I gave you all Israel and Judah. And if all this had been too little, I would have given you even more,” Nathan then accused David of his guilt in v. 9.

Why did you despise the word of the Lord by doing what is evil in his eyes? You struck down Uriah the Hittite with the sword and took his wife to be your own. You killed him with the sword of the Ammonites (2 Sam. 12:9).

True, David was guilty of adultery. But his coverup was even worse: He was guilty of deliberate, premeditated murder. “Despise” (Heb. bāzâ) in vv. 8 and 10 is a strong word meaning to disdain, deride, scorn, hold in contempt. When we go against God’s commands found in Scriptures, we elevate ourselves to a place of greater worth while demoting the worth of the Lawgiver’s words and values. When we sin willfully — doing something more than an inadvertent slip-up — we present ourselves as being independent of God’s rules, one who despises our Ruler, one who is in hearty rebellion.

Nathan Reads God’s Verdict and Sentence to David (vv. 10–14)

Nathan continued reciting God’s verdict to David in vv. 10–12. To his credit, David didn’t lie, make excuses, or rant thunderously at Nathan. Though he had the power to “kill the messenger,” he didn’t. His conscience had been wounded by his sin and coverup. Thankfully, his heart was still hungry for the LORD whom he’d rejected and whose words he’d despised. He therefore confessed immediately: “I have sinned against the LORD” (12:13a), to which Nathan responded, “The LORD has taken away your sin. You are not going to die. But because by doing this you have shown utter contempt for the LORD, the son born to you will die” (12:13b–14).

Clearly, God declared through Nathan the consequential punishment for David’s committed sins. Part of God’s sentencing required David and Bathsheba’s son to die, and that David’s sons were to follow in his footsteps of sexual sin and murder. It was a severe-yet-just penalty in God’s eyes.

It would be wise for us to notice how personally the LORD brings punishment: “. . . in broad daylight” (v. 12b). Realize that the LORD didn’t punish David immediately by zapping him from on high. Rather he used people directly, as he’d indicated he'd do in his Davidic Covenant, highlighted in this verse:

When he does wrong, I will punish him with a rod wielded by men, with floggings inflicted by human hands (2 Sam. 7:14).

God’s judgment and punishment here will come to pass when David’s son Absalom attempts to take the kingdom away from his father, while publicly sleeping with all of his father’s concubines (2 Sam. 16:21–22). Is God responsible for doing evil? No! In this case, as we’ll see in a few weeks, Absalom sinned against his father, David. God simply orchestrated those events.

† Summary of 2 Samuel 12:1–14

…by Jan van ’t Hoff at GospelImages

Click to enlarge and download this image of

Nathan telling David, “You are the man!”

from 2 Samuel 12:7a.

This passage recounts the prophet Nathan’s confrontation of King David following David’s adultery with Bathsheba and the orchestrated death of her husband, Uriah. God sends Nathan to David with a parable about two men: one rich and one poor. The rich man, possessing many flocks, selfishly takes the poor man’s only cherished lamb to prepare a meal for his guest (12:1–4). David, angered by the injustice, declares that the rich man deserves to die and must repay fourfold for the lamb (vv. 5–6). Nathan dramatically reveals, “You are the man!” and proceeds to expose David’s sin, reminding him of all God’s blessings and rebuking him for despising God’s commands by committing adultery and murder (vv. 7–9).

Nathan pronounces God’s judgment: Violence will arise from David’s own house, his wives will be given to another, and his secret sin will be exposed publicly (vv. 10–12). David humbly confesses, “I have sinned against the Lord” (v. 13), and Nathan assures him that God has put away his sin so he won’t die. Yet, there remains a tragic consequence — because David’s actions gave reason for God’s enemies to blaspheme, the child born to Bathsheba will die (vv. 13–14). This passage is a profound presentation of prophetic truth, personal repentance, and the interplay of mercy and justice in God’s dealings with his people.

Key points with verse references:

• Nathan rebukes David with a parable about a rich man unjustly taking a poor man’s lamb (vv. 1–6).

• Nathan reveals David’s guilt, reminding him of God’s blessings and confronting the gravity of his sin (vv. 7–9).

• God pronounces judgment: Violence and disgrace will arise within David’s house, and his sin will be exposed (vv. 10–12).

• David confesses his sin, and Nathan assures him of God’s forgiveness, but consequences remain (v. 13).

• The child born from David and Bathsheba’s union must die as a result of David’s actions (v. 14).

This Week’s Passage

2 Samuel 12:1–14

New International Version (NIV) [View it in a different version by clicking here; also listen to chapter 12 narrated by Max McLean.]

Summary Video: “The Second Book of Samuel”

† Watch this introductory video clip created by BibleProject on bibleproject.com.

- Q. 1 Why might it have been dangerous for Nathan the prophet to confront the king?

- Q. 2 How did David’s condemnation of the rich man’s greed help him acknowledge and condemn his own actions?