2 Samuel 10:1–19 . . . Bible Study Summary with Videos and Questions

“David Defeats the Ammonites, Then the Syrians”

Chapter 10 prepares us for David’s adultery with Bathsheba (highlighted in our next summary of ch. 11) by giving us the historical context in which that sin took place. It also shows David’s growing power that led to his sins. His increase in power had previously led to his sinful act of marrying Abigail (1 Samuel 25:39). Today’s references to Israel’s war with the Ammonites and Syrians frame the David and Bathsheba incident, giving the context for David’s sins.

This pair of military events must have taken place early in David’s reign, probably after showing his goodness to Mephibosheth (as shown in our ch. 9 summary) for his father’s sake. In this chapter’s example of David’s instance of showing kindness (Heb. hesed, v. 2; cf. 2 Sam. 9:1) to the Ammonites’ King Hanun, who was a non-Jewish Gentile, we learn that his act of goodness was neither appreciated nor reciprocated. The evidence for this is as follows.

It may be helpful to our understanding of the events of this chapter to establish the background for what was about to happen, by calling attention to several relevant facts: First, the peoples and the places mentioned herein surround the nation Israel — they weren’t distant places and peoples, but those near Israel, and they impacted Israel’s past, present, and future. Second, these are peoples and places that occupied the territory that God gave to Israel (see Genesis 12:1–3; 13:14–18), which the Israelites had neither overcome nor possessed. Third, these weren’t international super-powers but small kingdoms, much like city-states; to protect themselves and to promote their own interests, they had to enter into alliances with other small kingdoms. Fourth, we know from 7:1 that this was a time of relative peace. Fifth, David was acting on the basis of his promise, made in chapter 7, when he actively and aggressively set forth to subdue Israel’s enemies and obtain the liberty and land that God had promised.

[Note: Click the link to This Week’s Passage near the bottom of this page to read today’s Scripture.]

One Stupid Mistake Starts a War (2 Samuel 10:1–4)

Up to this point, David had an alliance with the king of Ammon, whose capital was at Rabbah (Rabbath-Ammon). In chapter 8, we saw David take the initiative, subjecting his enemies who surrounded Israel. In chapter 10, David was virtually forced to fight with some who were formerly his friends. The central figure in this chapter is Hanun, the son of Nahash, the deceased king of the Ammonites.

We first met Nahash in 1 Sam. 11 where he and his army had besieged Jabesh Gilead and threatened to settle for peace only if they gouged out the right eye of every man in the city. Saul rose to the occasion, empowered by the Spirit of God, and led Israel to victory over Nahash and the Ammonites. Nevertheless, they weren’t eradicated; in time, King Nahash became David’s ally and a friend. David had every intention of honoring the formerly friendly king when he sent a delegation to mourn Nahash’s death at Rabbah, expressing his sympathy and cementing good relations with Hanun, King Nahash’s son, who’d begun to reign on his father’s throne.

Before King Nahash of Ammon died, he’d threatened Jabesh Gilead at the start of King Saul’s reign (1 Sam. 11:1–11). Therefore, he reigned for more than than 40 years. However, he must not have reigned much longer than that. If he’d done so, he’d have had an unusually long reign. Furthermore, when the Ammonites humiliated David’s soldiers (v. 4), they showed no fear of Israel. This would have been their reaction only at the beginning of David’s reign, not after he’d subdued all his enemies.

Hanun, King Nahash’s son, wasn’t like his father. It seems he had little desire to maintain the status quo in his relationship to David or the Ammonites relationship to Israel. It was early in Hanun’s reign that David sent a delegation to Ammon, to convey his respect for Nahash and mourn his death. David’s intention in v. 2 to “show kindness to Hanun” should remind us of David’s showing kindness to Mephibosheth; see our previous summary. His kindness to people didn’t end with what he’d done for Mephibosheth. Here we learn that David showed kindness towards a pagan king because he genuinely sympathized with the man’s loss of his father.

Advisors of this newly installed king give him some bad counsel; they assured him that David’s intentions weren’t honorable because he’d sent these men as spies to obtain intelligence to help with a future attack. It’s possible that this explanation of events gave Hanun the excuse he was looking for, a reason to break the alliance his father had made with David and Israel. If Hanun had hearty expansion plans of his own, he’d have to go to war with David. If he could defeat David, he’d gain control over all of those nations that David had defeated and subjected.

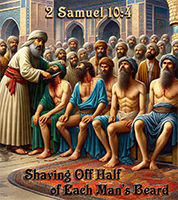

As we look at details in v. 4 (see image left), Hanun probably had the beards of David’s messengers half-shaved to make them look very foolish (cf. Isaiah 7:20). Military victors sometimes also humiliated their captives by exposing their buttocks (cf. 20:4). Nahash thoroughly humiliated David’s well-meaning delegates by cutting off their robes in such a way that their nakedness would be exposed. Then, Nahash sent them home in disgrace. How stupid was he! A wise ruler wouldn’t insult the most powerful king in his region.

It’s probable that Nahash also removed the tassels from the soldiers’ garments that identified them as Jews (cf. Numbers 15:37–41). Notice that Hanun’s advisors assumed David’s worst motives rather than his best, which is a temptation that many people today face. Remember: As the hair on Samson's shorn head ultimately grew back (Judges 16:22) and proved to be a bad omen for the Philistines, so also the regrowth of the beards of David’s men would suggest upcoming disaster for the Ammonites.

David’s Response to Hanun’s Stupidity (vv. 5–7)

David received word that his delegation had been abused and humiliated (v. 5). Their beards were, for the Hebrews, a universal mark of a man’s greatest ornament and his dignity. But Hanun not only had the beard of each man shaved off embarrassingly, he also had their garment bottoms cut off, to further ridicule them. To insult a king’s ambassador amounted to insulting the king himself. It was just as if they’d done this to King David.

It’s one thing to conclude that a delegation had come for less-than-noble reasons. It’s quite another to deliberately humiliate such a delegation and provoke an outright war with Israel. Eventually, however, the Ammonite king realized the level of his stupidity. In order to defend his kingdom of Ammon from David’s inevitable retaliation, he paid some of his allies to send him their armies: Beth Rehob and Zobah sent 20,000 Aramean foot soldiers from a kingdom that David had previously subdued (2 Sam. 8:3–8); Maacah sent 1,000 men; and Tob sent 12,000 men.

Understandably, Hanun hired these additional troops to protect his borders and enhance security. But to have humiliated David’s delegation, who must have been protected by what we’d call “international law” and “rules for diplomats,” was to ensure conflict. Hanun apparently picked a fight. If that was his plan, it worked but it failed in that it brought about not only a defeat for the Ammonites, it served to dishearten their Syrian allies, who’d no longer come to their aid.

David took pity on his dishonored delegation. He didn’t use these men as political tools to whip up anger against the Ammonites. He cared more for their dignity and honor, so he sent messengers to meet them, instructing the delegates to wait in Jericho till their beards grew back before returning to Israel. The author doesn’t say that David, intending to go to war, summoned his troops. We’re told only that Ammonites recognized that they’d “become obnoxious or odious to David” (v. 6a) — they’d made themselves repulsive to Israel. Rather than apologize or attempt to reconcile themselves with him, they attempted to make an alliance that would strengthen them in their conflict with Israel. Syrians from several regions were hired as mercenaries (v. 6b). Only after David learned of this military buildup did he call his army into active duty (v. 7).

The fact that Zobah, Aramea, and other northeastern enemies of Israel would ally with Ammon (v. 6) suggests that this event took place before David had brought them under his authority (v. 19; cf. 8:3–8). Perhaps 993–990 BC are reasonable dates for the Ammonite wars with Israel. We ought to also note in the text that there was no explicit consultation of Yahweh before engaging in warfare, as the author described previously in 2:1.

On the Battle Fronts (vv. 8–19)

David responded to the Ammonites’ insult by engaging his entire army, under Joab, who had only one battle strategy: attack. Many generals would have considered surrender when surrounded on both sides by the enemy, but not Joab. He called the army to courage and faith and told them to press on. His forces drew up battle lines against the Ammonites and their Syrian mercenaries. Such a coalition army divided itself into two groups, intending to attack the Israelites from the front and rear. The Israelite army was in extreme jeopardy! When Joab realized this, he too divided Israel’s army into two forces to fight a two-front battle. He said, “Be strong, and let us fight bravely for our people” (v. 12), leading one division while his brother, Abishai, led the other; Joab set against the Syrians; Abishai against the Ammonites. If either Israelite military group became hard-pressed by its opponent, the other group was to come to the other’s aid.

In Joab’s words to his troops, you can sense the seriousness of the situation. They were in a fight for their lives. His words of vv. 11–12 evidence their strong faith in God before they set out for battle:

11Joab said, “If the Arameans are too strong for me, then you are to come to my rescue; but if the Ammonites are too strong for you, then I will come to rescue you. 12Be strong, and let us fight bravely for our people and the cities of our God. The LORD will do what is good in his sight” (2 Sam. 10:11–12).

Joab wisely prepared for the battle to the best of his ability and worked hard for the victory. At the same time, he knew that the outcome was ultimately in God’s hands. And God was with them! When Joab advanced on the Arameans, they fled, and the Ammonites then retreated into their city to avoid slaughter. Rather than put the walled city under siege at this point, Joab returned to Jerusalem. The Israelites had won the first round, though the Ammonites remained a dangerous enemy on Israel’s eastern borders.

We see in vv. 13–14 that it doesn’t say that Joab actually engaged the Syrians in battle. Instead, we learn only that this mercenary army fled before the army of the mighty men because God was with them. God promised this kind of blessing upon an obedient Israel (Deuteronomy 28:7). When the Ammonites saw this, they lost heart as well. In the end, the Syrians fled home, the Ammonites headed for the protection of their chief city, Rabbah, and the Israelites returned to Jerusalem. David appeared willing to leave it at that, but the Syrians hadn’t yet learned their lesson. They, like the Philistines (in chapter 5), weren’t willing to give up after one defeat; they wanted a rematch and they got it, only to lose again, more decisively. The Syrians assumed they could win this time if they brought in more Syrians from “beyond the Euphrates River” (v. 16), led by Hadadezer who’d had a grudge of his own to settle with David (see 2 Sam. 8:3).

David was aware that he had more than the Ammonites to cope with. His regrouped Aramean vassals, under King Hadadezer of Zobah, were in full rebellion, trying to throw off David’s yoke. Hadadezer called on troops from Aramean allies north of the Euphrates River (ancient Mesopotamia) and they assembled for battle at Helam, east of the Jordan, with Zobah’s chief general in command. It was a huge force, with tens of thousands of soldiers and hundreds of chariots.

Instead of leaving Joab to fight this huge battle, David realized that another attack was imminent so “he gathered all Israel and crossed the Jordan” (v. 17). The rematch was staged. Israel’s massed troops crossed the Jordan at a ford and marched towards the Arameans who were massed at Helam. Once again the Syrians fled from David and his army; this time their defeat was even greater than before. We don’t know the details of the battle, but we know the result: David killed 700 charioteers and 40,000 horsemen; he also killed Shobach, the Syrian army’s commander. It was a decisive victory! As a result, all the city-states and kingdoms that had been loyal to Hadadezer of Zobah transferred their allegiance to David and became his vassals. “So the Arameans were afraid to help the Ammonites anymore” (v. 19b). The Syrians finally got the point that it doesn’t pay to attack God’s people or to fight against God’s king. The surviving kings made their peace with David. The Syrians determined that they wouldn’t make that mistake again but would align themselves with the Israelites. The Ammonites hadn’t yet become subjected to David. This will come about in chapters 11 and 12.

Chapter 10 ends with unfinished business at Rabbah. The offending Ammonites remained in their city while Joab had returned to Jerusalem. In the spring, King David would send Joab and Israel’s army out again to deal with Rabbah while he chose to stay in Jerusalem. While living comfortably their during that next war, David fell into sin with Bathsheba. Most of us know about David’s sin with her, and how it happened when David waited in Jerusalem instead of leading the battle at Rabbah. We see in this chapter that God gave David a warning: It was necessary for him to go out and fight against the Syrians. David tried to leave Joab to fight on his own, but Israel’s army needed David, so God tried to show him that need by blessing each battle’s outcome when David actually engaged in warfare. Also in this chapter we see God’s gracious forewarning that David sadly failed to realize. [Stay tuned for details of that adulterous account in next week's summary titled “David and Bathsheba.”]

† Summary of 2 Samuel 10:1–19

This nineteen-verse passage recounts the escalation of hostilities between Israel and the Ammonites, triggered by a diplomatic misunderstanding. After the death of Nahash, king of the Ammonites, David attempts to extend kindness to Hanun, Nahash’s son, as a gesture of goodwill for past loyalty (vv. 1–2). Hanun’s advisers sow distrust, convincing him that David’s envoys are spies, which leads Hanun to shamefully abuse the messengers by shaving half their beards and cutting off their garments — an act considered deeply dishonorable (vv. 3–5). The affront prompts the Ammonites to prepare for war by hiring Aramean (Syrian) mercenaries from Beth Rehob, Zobah, Maacah, and Tob (v. 6).

In response, David sends Joab and the entire army to confront this threat. The Israelite army finds itself encircled by both the Ammonites and their Aramean allies, so Joab divides his forces between himself and his brother Abishai to fight on two fronts (vv. 7–10). Joab encourages the troops to trust in God’s outcome and act with courage (vv. 1– 12). The Arameans flee from Joab’s advance, and once the Ammonites see this, they retreat into their fortified city (vv. 13–14). Later, the Arameans regroup and bring out reinforcements, but David personally leads Israel to a devastating victory, inflicting massive casualties and subjugating the Arameans, who make peace and serve Israel (vv. 15–19).

Key points with verse references:

• David shows kindness to Hanun, king of Ammon, after Hanun’s father’s death (vv. 1–2).

• Hanun humiliates David’s envoys by shaving their beards and cutting their garments (vv. 3–5).

• The Ammonites hire Aramean mercenaries to fight Israel (v. 6).

• Joab divides Israel’s army to fight the Ammonites and Arameans, encouraging courage and faith (vv. 7–12).

• Israel’s victory is led by Joab and David, resulting in the Arameans’ submission and peace with Israel (vv. 13–19).

This Week’s Passage

2 Samuel 10:1–19

New International Version (NIV) [View it in a different version by clicking here; also listen to chapter 10 narrated by Max McLean.]

Summary Video: “The Second Book of Samuel”

† Watch this introductory video clip created by BibleProject on bibleproject.com.

- Q. 1 Who started the war between the Ammonites and the Israelites? . . . Why?

- Q. 2 How does Joab manage the war on two fronts (vv. 9–11)?

- Q. 3 Just as Joab relied on reinforcements, where do you feel the need for reinforcements?