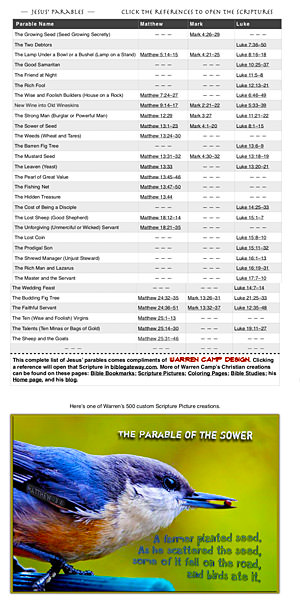

The Parable of the Great Banquet is found in Luke’s gospel. It’s similar to the Parable of the Wedding Banquet (Matthew 22:1–14), but has some significant differences.

Incidentally, Jesus spoke about the heaven-or-hell judgment more than anyone else in the Bible and in a very specific way. More than half of the parables that Jesus told relate to God’s eternal judgment of sinners.

— Preview —

Click the list or the “bird” to enlarge and use Warren’s list of forty-four of Jesus’ parables (a PDF file with links to Scriptures).

par•a•ble [noun] a simple story used to illustrate the meaning of or a moral or spiritual lesson, as told by Jesus in the gospels

synonyms: allegory, moral story/tale, fable

Jesus’ Parable of the Great Banquet

Luke 14:15–24 NIV

Putting this parable into context to appreciate its meaning, we need to realize that Luke’s account (as opposed to Matthew’s 22:1–14, which has Jesus walking on the road to Bethany) was told at a dinner that Jesus attended. In Luke’s account, Jesus had just healed a man with dropsy (edema, swelling) and taught a brief lesson on serving others. He then said that those who serve others “will be repaid at the resurrection of the righteous” (14:14). At the mention of the resurrection, someone at Jesus’ table said, “Blessed is the one who will eat at the feast in the kingdom of God” (v. 15). In reply, Jesus told the Parable of the Great Banquet (or Feast).

The basic message of this parable could be this: “The tragedy of the Jewish rejection of Christ had opened the door of salvation to the non-Jewish Gentiles. Today, as well, the blessings of the kingdom are available to all who’ll come to Christ by faith.”

This entertaining 2-minute video comes compliments of CCO Youth

The Parable of the Great Banquet

A Parable of Judgment

We see in Luke 14:1 that Jesus went to enjoy a Sabbath dinner at a prominent Pharisee’s house, likely filled with the Pharisee’s socially elite guests, all of whom were experts in the Law. In response to a man at the table with him saying, “Blessed is the one who will eat at the feast in the kingdom of God” (v. 15), Jesus began to speak this parable. Two important elements to note here: (1) This was to be a “great” banquet, and (2) “many guests” had been invited. The host had planned a great feast in a room or hall that was large enough for numerous guests. (See the enlarged photo at the bottom of this page of the painting by an anonymous Flemish painter, circa 1525, of this filled banquet hall.)

What you may not realize is one of the cultural practices of that time. When a man was going to give a banquet, he sent out an invitation weeks or months in advance. If it was a marriage banquet, his invitations went out soon after the betrothal, almost a year in advance.

It’s also important to realize that, in Jesus’ day, gala dinner invitations were made using a two-part effort: (1) the initial invitation was made to guests, an appreciable amount of time before the day of the banquet, and (2) a follow-up personal summons to the event was later made, when all the meal’s preparations had been completed and the feast was about to begin. Once the host determined how many guests had accepted his invitation, he’d be able to determine how many animals to kill and cook. As v. 16 documents, “many guests” had been invited to this big feast.

In this parable, a “certain man” who’d planned a large banquet had already sent out invitations to it. As the banquet event was about to begin, the man sent his servant out to find each of the invited guests and summon them, telling them that all was ready and the feast was about to begin for everyone’s enjoyment (vv. 16–17).

The Parable of the Great Banquet

15When one of those at the table with him heard this, he said to Jesus, “Blessed is the one who will eat at the feast in the kingdom of God.”

16Jesus replied: “A certain man was preparing a great banquet and invited many guests. 17At the time of the banquet he sent his servant to tell those who had been invited, ‘Come, for everything is now ready.’ (Luke 14:15–17).

Jesus says in his parable that the feast’s invited guests began to make excuses to the servant for their not attending: One had just bought a piece of land and said he had to go see it (v. 18); that man was concerned with financial investments, but surely, no one buys a field sight unseen. Another who’d purchased ten oxen said that he was on his way to yoke them up and try them out (v. 19); that man was preoccupied with his business, but no one would buy five pairs of oxen without first verifying that they were capable of the work expected of them. Both excuses were flimsy and meritless; each indicates an extent of self-interest in finances and perpetuating worldly riches, on both men's parts. Purchasing property was and is a wealthy man’s luxury; and five yoke of oxen would have been suitable for an estate, while one or two pairs of oxen would be adequate for a small farm.

The third guest’s excuse was that he’d become newly married and, as a result, he couldn’t attend the great banquet (v. 20). His concern focused on his family matters. That was also a lame excuse because, when he accepted the invitation, he likely would have known of his wedding plans. In that case, it would have then been the time for him to politely decline the dinner invitation. But for him to back out at the last minute would have been an outright act of rudeness to the generous host.

The behavior of all three invited guests would have been representative of the behavior of all of the many invited guests who chose not to attend. The Greek phrase used, apo mias pantes, means “from the first, all. . .” confirming that the rejection was unanimous. The excuses were lame (as the video above highlights). The three excuses that Jesus mentioned were representative of the rest.

18“But they all alike began to make excuses. The first said, ‘I have just bought a field, and I must go and see it. Please excuse me.’

19“Another said, ‘I have just bought five yoke of oxen, and I’m on my way to try them out. Please excuse me.’

20“Still another said, ‘I just got married, so I can’t come’ (vv. 18–20).

In light of the social cultures and morays of Jesus’ day, for an invited guest to fail to attend a banquet in which he’d previously indicated acceptance would have been a grave breach of social etiquette, an outright insult to the host. In a society where one’s social standing was determined by peer approval, often based on who was invited to whose dinner, such a failure to honor and accept the host’s invitation would have amounted to an explicit slap in the face. Add to that, for a large collection of dinner guests to reject the second invitation — the final summons — would have appeared to be a conspiracy to discredit the host.

Quite expectedly, the man of the house became angry when he heard those flimsy excuses. There’s no blaming the host for being angry when he heard of this rude affront and unanimous rejection by his social peers. So he told his servant to do what would have been social suicide had he not already received a multitude of rejections: invite lower-class people to his great banquet. He ordered his servant to ignore the guest list and rush out to the town’s back streets and alleyways, and invite “the poor, the crippled, the blind and the lame” (v. 21).

21“The servant came back and reported this to his master. Then the owner of the house became angry and ordered his servant, ‘Go out quickly into the streets and alleys of the town and bring in the poor, the crippled, the blind and the lame.’

22“‘Sir,’ the servant said, ‘what you ordered has been done, but there is still room.’

23“Then the master told his servant, ‘Go out to the roads and country lanes and compel them to come in, so that my house will be full’” (vv. 21–23).

The first sweep of personal summonses was made in town and included “broad, main streets or public squares” (Greek plateiai) and “narrow streets, lanes, alleys” (Greek rume). After the servant brought in many of the town’s down-and-out citizens, the master realized that there was still room in the banquet hall for additional guests. So he told his servant to “Go out to the roads and country lanes and compel them to come in, so that my house will be full” (v. 23). That second sweep was made outside the town in rural areas, the, “road, country lanes” (Greek hodos) and “fences, hedges” (Greek phragmos). Inside the town would have been the poor, the beggars, the crippled; outside the town would have been the vagabonds and itinerants, often those who became shunned and unwelcome in the towns.

Realize that the master hadn’t sent out soldiers to sweep the area, round up everyone, and march them to his house. But he instructed his servants not to take No for an answer. The Greek word used is anagkazo, which means to “compel, force, . . . strongly urge/invite, press.” The host insisted on having a full house at his great banquet.

The element of judgment arises when we see and feel the emotion that Jesus probably expressed in his parable’s closing verse, wherein the master (albeit the Master) declared: “I tell you, not one of those who were invited will get a taste of my banquet” (v. 24). That concluding sentence is filled with hurt and anger at having been rejected.

Who’s Who in This Parable?

The master of the house Clearly in Jesus’ presentation of this judgment parable, the host and master of the house is God the Father, who invited his people, Israel, to the messianic banquet in the kingdom of God.

The great banquet hall Jesus wanted his parable listeners then, and his parable readers today, to realize that he was highlighting the kingdom of God, as we see in the blessing that one of those sitting at the banquet table with Jesus said to him.

The invited guests God’s kingdom had been prepared for the people of Israel. The banquet’s invited guests — the rich and social elite — represent the Pharisees and Jewish religious establishment. Their Jewish nation had been those whom God had historically invited to relate personally with him through his covenant. Many of the invited Israelites refused to obey God’s covenant, thereby worshiping false gods (Jeremiah 3:6–10; Ezekiel 16:15) or not obeying the commandments, thus refusing to accept God’s invitation. When the Master said in v. 17b, “Come, for everything is now ready,” he was reminding the Israelites of what he’d been telling them repeatedly: “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven has come near” (Matthew 4:17). Yet, while he preached about the kingdom of heaven being near, the Jewish nation as a whole rejected him and his teachings.

The poor, maimed, and downtrodden These are the common people, considered “unclean” by the Pharisees. Perhaps those people inside the town were Jews while those in the outlying areas were non-Jews. No matter, they were receptive to the Master’s invitation and gained much from attending the great feast.

A Hearty Way to Approach and Apply This Parable

The master wasn’t satisfied with a partially full banquet hall; he wanted every place at the table to be filled. The guests’ excuses were lame for a variety of reasons (as documented on gotquestions.org.): “The excuses for skipping the banquet are laughably bad. No one buys land without seeing it first, and the same can be said for buying oxen. And what, exactly, would keep a newly married couple from attending a social event? All three excuses in the parable reveal insincerity on the part of those invited. The interpretation is that the Jews of Jesus’ day had no valid excuse for spurning Jesus’ message; in fact, they had every reason to accept Him as their Messiah.”

While we understandably feel bad when we’re rejected, think how the Father feels when he’s rejected. Father God must be filled with grief and likely gets his heart broken when he sees each rejection of him and his kingdom. In addition to thinking of his anger, imagine well his mercy and grace. After all, today’s unworthy souls — sinners such as us who’ve yet to appreciate who the Master can become in our lives — are also continually invited to come to the Master’s table. “Blessed is the one who will eat at the feast in the kingdom of God” (14:15b).

It’s important to appreciate the fact that the Master’s subsequent invitations were sent to the poor, crippled, blind, and lame. It was that collection of society whom the Pharisees considered sinful outcasts. But Jesus challenged that way of thinking, teaching his audiences that the kingdom of God was indeed available to anyone, even the “unclean” whom the Jewish leaders deemed to be cursed by God. The fact that this parable’s Master had sent his servant far afield to persuade everyone to come indicates that the Lord’s offer of salvation extended to the Gentiles in his region and certainly “to the end of the earth” (Acts 1:8b).

By their own free will, and for whatever reason, those who ignored the master’s invitation to the banquet chose their punishment. The parable’s master respected and accepted the guests’ choice and chose to make it permanent by saying that they wouldn’t “get a taste of my banquet” (v. 24b). Their deliberate rejection of God’s invitation into his kingdom brought greater judgment on them, which is disappointing for those of us who’ve genuinely accepted his invitation and entered his presence.

So it’ll be with God’s judgment on those who choose to reject Christ: They’ll make their choice and God will confirm it; those who reject him and his kingdom will never taste the joys of heaven. They’ll instead perpetually endure the torment of hellfire. Be most thankful if you’re one of the Master’s invited guests who’s accepted his personal invitation to join him and who will enjoy the feast he offers you at his great banquet.

Questions From your experience, what excuses do people make to avoid God’s “banquet”? What can you say or do to help people overcome their hesitation?

“Go out to the roads and country lanes and compel them to come in, so that my house will be full” (Luke 14:23).